|

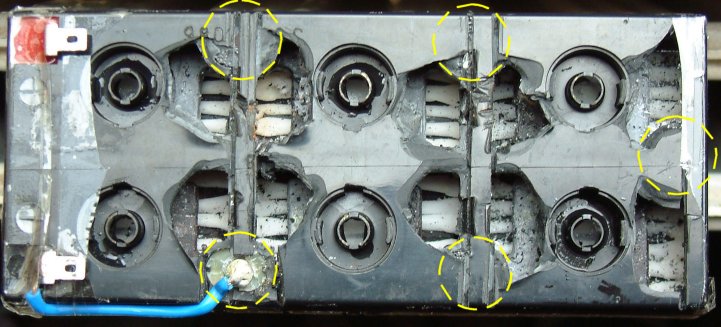

Slowly and carefully drill a hole of depth 4-5mm at position 1 using a 1-1.5mm HSS drill bit. The idea is to access the interconnection terminal. I then stick the end of a straighten paper clip into the hole and measured the voltage between the paper clip and either the positive or negative terminal. With the voltmeter still connected, the load or resistor is applied across the measurement point. If the voltage reading falls only a little, this part of the battery is good. After finding out which three series cells of the battery is faulty, drill another hole on the faulty (3 series cell) path and repeat the procedure. The figure above showed the drilling sequence if one of the top 3 cells are faulty.

Well the idea is to find the failed cell, and drill as few holes as possible. If more than one cell have failed, the battery is not worth furthur effort and can be discarded. When I find the failed cell, I enlarge the two holes across the failed cell using a 2.5mm bit. Using a 3mm tap, I carefully thread the hole and screwed in two 3mm copper screws. Using the highest current range of the multimeter, I measured momentarily the current between the two copper screws and confirm zero current is flowing. A jumper wire soldered to the screw tops complete the battery circuit and allow the battery to function at 10V. Remember not to connect the now 10V battery to a 12V battery charger.

Seal all holes and around the screws with sealant afterwards. |